It’s not just a phase! One tool that QC gives us is an entirely new dimension to work with, which we call phase.

Note: this post is part of my series, Programming the Multiverse

We’ve looked at the internals of a couple gates but let’s dive into the Hadamard gate. Here is its internal magic matrix:

\[\left[ \begin{array}{cc} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \end{array} \right]\]Wait, what’s up with that negative \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\)?!

Remember our qubit in the \(\ket{0}\) state, represented by \(1\ket{0} + 0\ket{1}\). If we put it through the H gate, we get:

\[\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left[ \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{c} 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left[ \begin{array}{c} 1 \\ 1 \end{array} \right]\]Note: the \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\) in front of the matrix is a shortcut for having to write the fraction four times inside the matrix. It’s a distributive multiplication on all the items.

Now let’s feed it a qubit in the \(\ket{1}\) state, represented by \(0\ket{0} + 1\ket{1}\).

\[\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left[ \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right] = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left[ \begin{array}{c} 1 \\ -1 \end{array} \right]\]So this means we have a qubit in this state: \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\ket{0} - \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\ket{1}\) or generalized as \(a\ket{0} - b\ket{1}\). That negative b indicates a negative phase.

A new dimension

Earlier I mentioned that a qubit is like a spinning die where you might decide a roll of 1 through 3 represents a classical bit equal to 0 and a roll of 4 through 6 represents a classical bit equal to 1.

Phase is like each die having a color you can control with a dial. You can spin the dial to cycle through an infinite number of shades. Phase does not directly affect the probability of whether the qubit is a \(\ket{0}\) or a \(\ket{1}\). But you can use the phase for various tricks.

When we have a negative phase, it’s not setting the phase to a negative numeric value, but it is saying “the phase of your qubit has an opposite phase value compared to the global phase that all the qubits started out in.” We’ll see later that putting two qubits with opposite phase through certain gates causes certain \(\ket{0}\) and \(\ket{1}\) combinations to cancel out.

If you look at the color wheel, you can think of qubits with opposite phase having complementary colors on the color wheel. Complementary colors look good next to each other but combining them results in a yucky brownish color. Other color combinations mix better to form new colors.

Getting kickbacks

Our first trick using phase is called phase kickback. This phenomenon applies to “controlled” gates like the CNOT. Let’s see how it works.

In order for the kickback to happen, the phase of the target qubit has to be negative. Its phase then gets transferred or “kicked back” up to the control qubit when the gate is applied.

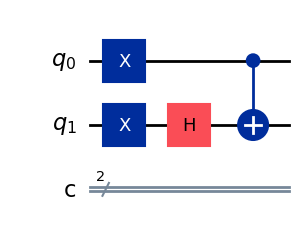

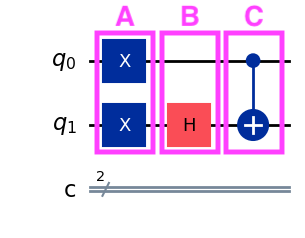

Let’s create a circuit that does just that. To start out, we need both our qubits initialized to \(\ket{1}\) and we need to get our target into a negative phase (yes we’ll turn our qubit into a goth kid). We’ll use our handy H gate for that. By running this circuit we’ll copy the negative phase of \(q_1\) into \(q_0\).

Here’s the code to generate the above circuit:

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, QuantumRegister, ClassicalRegister

from qiskit_aer import Aer

from qiskit.visualization import array_to_latex

q = QuantumRegister(2, 'q')

c = ClassicalRegister(2, 'c')

qc = QuantumCircuit(q, c)

qc.x(0)

qc.x(1)

qc.h(1)

qc.cx(0,1)

You can view the code for this part here.

Let’s use Qiskit’s statevector output to see what \(q_0\) and \(q_1\) look like after applying the gates:

from qiskit.quantum_info import Statevector

Statevector(qc).draw('latex')

When we examine our resulting state vector, we see:

\[- \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \ket{01} + \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \ket{11}\]IMPORTANT: Qiskit does something really weird that’s important to know - it reverses the order of the qubits when it prints statevectors and run results. So where all the mathematical literature uses \(\ket{q_0 q_1}\), Qiskit displays \(\ket{q_1 q_0}\). They claim it’s because they consider \(q_n\) the most significant bit when you use qubits to represent binary numbers, but I think they’re really just trolling people. If you want to output it in conventional order you can use:

Statevector(qc.reverse_bits()).draw('latex')

So \(- \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \ket{01} + \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \ket{11}\) respresents the probabilities of the combined states of \(q_0\) and \(q_1\). Remembering that we square the probability amplitudes to get our probabilities of each state, we get a 50% chance where \(q_0 = -\ket{1}\) and \(q_1 = -\ket{0}\). This means our CNOT flipped \(q_1\) from \(\ket{1}\) to \(\ket{0}\) but \(q_1\)’s negative phase going into the gate got copied up to \(q_0\). Rad!

So what’s actually going on in the land of matrices?

In this post we let Qiskit/python do all the matrix math here, but it’s interesting and useful to show how you would actually use matrix multiplication to represent what just happend.

A quick look at how to calculate multiple gate operations

Previously, in part 4, we multiplied a single qubit’s state vector times a single gate matrix. In order to work with a gate that operates on multiple qubits, we did some simple tensor products on the qubits’ individual state vectors to generate a combined state vector.

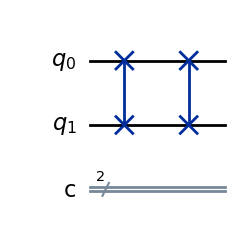

But now that we have multiple gates in a row, we have to do some more tricks. We have to do a dot product between the series of gates and the state vector. Let’s see how this works for two SWAP gates in a row:

When we have gates in series, we do a dot product of each gate’s matrices in reverse order and we multiply them by the initial state vector which is always the last item in the equation. For our example, let’s say \(q_1 = \ket{1}\).

\[\overbrace{ \left[ \begin{array}{cccc} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right] }^{\text{SWAP 2}} \cdot \overbrace{ \left[ \begin{array}{cccc} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right] }^{\text{SWAP 1}} \cdot \overbrace{ \left[ \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] }^{\text{Current State } \ket{01}}\]We’ll start by multiplying the initial state by SWAP 1. We now get:

\[\overbrace{ \left[ \begin{array}{cccc} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right] }^{\text{SWAP 2}} \cdot \overbrace{ \left[ \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] }^{\text{Current State } \ket{10}}\]Notice that our statevector represents \(\ket{10}\). Finally, finish multiplying the current state by SWAP 2 and we get:

\[\left[ \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right]\]And we’re back to \(\ket{01}\). Our double-swap left our two qubits back in their original state.

If we had started from the left side and multiplied our two SWAP gates, we would get:

\[\left[ \begin{array}{cccc} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right]\]Notice that cool pattern of ones along the diagonal? That’s called an identity matrix. It means the matrix does not change a vector you do a dot product with. So our original state vector is unchanged after two swaps, as we’d expect.

When gates are uneven

In our kickback example, we did different gate operations on each qubit. So how do we represent that with matrices? If you said, “let’s use the same tensor product alchemy we used to create our 4-row state vector from two qubits” you’d be exactly right!

Looking at our kickback diagram, we have 3 columns of gates:

The entire circuit (the “composite system”) can be built from the following equation:

\[\ket{\Psi} = C \cdot B \cdot A \cdot (q_0 \otimes q_1)\]The columns are in reverse order because we’re doing a dot product of the gate matrices on the initial state vector and need to preserve the dimensions of the state vector throughout.

For \(A\) we can do a tensor product of the two X gates:

\[A = \overbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} }^{q_0 \text{ X Gate}} \otimes \overbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} }^{q_1 \text{ X Gate}} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\]For \(B\) we need to use some cleverness. Nothing happens to \(q_0\) in column B, right? That means that we can think of it as if we applied one of those identity matrices that does nothing to the qubit! So just like we did a tensor product for A, we’ll do it for B between the identity and the H.

\[B = \overbrace{ \left[ \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{array} \right] }^{\text{Identity}} \otimes \overbrace{ \left[ \begin{array}{cc} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \end{array} \right] }^{\text{H Gate}} = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 \end{bmatrix}\]For \(C\) we just use the regular CNOT matrix since it spans all our qubits.

Our full equation is:

\[\ket{\Psi} = \overbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix} }^{\text{C (CNOT)}} \cdot \overbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} & \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} & 0 & 0 \\ \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} & -\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} & \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \\ 0 & 0 & \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} & -\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \end{bmatrix} }^{B} \cdot \overbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} }^{A} \cdot \overbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ \end{bmatrix} }^{\ket{00}}\]One thing to note here is that as the number of qubits increases, the size of the matrices needed to represent the whole quantum circuit exponentially increases. It becomes apparent that to simulate a quantum computer with a classical computer doing matrix multiplication it requires a ton of computing resources to execute. In fact, simulating around 50 qubits (requiring \(2^{50}\times2^{50}\) matrices) becomes impossible with today’s classical supercomputers.

The kickback in action

So back to the question, how does the phase get kicked back from the control input into the target input?

Let’s multiply our A and B matrices with the initial state to calculate what happens up until the point where we send the qubits throught the CNOT gate.

\[\ket{\Psi} = \overbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix} }^{C} \cdot \overbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \\ - \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \end{bmatrix} }^{\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\ket{10} - \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\ket{11}}\]Notice the negative phase on the state where \(q_0 = \ket{1}\) and \(q_1 = -\ket{1}\). The other state means our H gate flipped \(q_1\) to be \(\ket{0}\) so we lose the negative phase.

When we expand out the matrix multiplication, we get:

\[\ket{\Psi} = \begin{bmatrix} (1\times0) + (0\times0) + (0\times\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}) + (0\times-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}) \\ (0\times0) + (1\times0) + (0\times\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}) + (0\times-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}) \\ (0\times0) + (0\times0) + (0\times\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}) + (\textcolor{red}{1\times-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}}) \\ (0\times0) + (0\times0) + (1\times\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}) + (0\times-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}) \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ \textcolor{red}{-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}} \\ \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \\ \end{bmatrix}\]So there we go, we went from a state of \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\ket{10} - \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\ket{11}\) to a new state of \(-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\ket{10} + \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\ket{11}\). In the next article, we’ll see how we can use this neat trick.